Overview

Rambling

Whew! It’s been about 2 weeks since the 2019 PowerShell + DevOps Global Summit - the first conference I’ve played a role in organizing. It was super fun, and it was an honor to get a chance to help with content for the summit… that said, it’s been a nice two weeks of recovering!

A lot of folks asked what I do nowadays! I gave my usual :headtilt: computers? response, but the gist of it is, while I still do quite a bit with PowerShell, I have a bunch of other building blocks to design solutions with! One of the more fun ones has been Elastic Stack.

So! Today we’ll dive into using Winlogbeat and ingest pipelines, in case it saves anyone else from wading through disparate documentation with no clear layout of an end-to-end example.

Disclaimer: I know way, way less about logging and Elastic Stack than I do about PowerShell.

Overview

Hopefully, you already have structured logging. If you don’t, or if you’re paying Splunk-level-money, my condolences.

Things we won’t be talking about today:

- How important structured logging is, the many critical use cases that it enables, or any of that jazz. I assume you know it’s important

- Spinning up a cluster, or even a single test node. You can find that elsewhere

- PowerShell

So… what are we going to talk about? We’re going to show a slightly-more-useful config than the vanilla Winlogbeat examples you see out there, including:

- how to filter log sources before sending them on to Elasticsearch

- how to point logs at ingest pipelines

- how to create an ingest pipeline

Let’s get going!

Winlogbeat

We tend to use Elastic Beats clients - there are other options out there, including NXLog.

We’ll use Winlogbeat in this example. There are a few pieces we’ll dive into:

- what logs we care about

- whether any of the logs need to be processed in a pipeline

- whether to process anything on the client

What we care about

So! First, we’ll tell Winlogbeat what we care about, and tack on information about which pipeline to ship logs to.

winlogbeat.event_logs:

- name: Security

ignore_older: 168h

fields:

rc_ingest_pipeline: 'windows'

rc_index_name: 'windows'

fields_under_root: true

- name: 'Microsoft-Windows-DNS-Client/Operational'

ignore_older: 168h

processors:

- drop_event.when.not:

and:

- equals.event_id: 3008

- and:

- not.equals.event_data.QueryOptions: '140737488355328'

- not.equals.event_data.QueryResults: ''

- name: System

ignore_older: 168h

processors:

- drop_event.when.not:

or:

- equals.source_name: 'Microsoft-Windows-Eventlog'

- and:

- equals.source_name: 'Microsoft-Windows-GroupPolicy'

- equals.level: Error

- or:

- equals.event_id: 1085

- equals.event_id: 1125

- equals.event_id: 1127

- equals.event_id: 1129

- and:

- equals.source_name: 'Microsoft-Windows-Eventlog'

- equals.level: Information

- equals.event_id: 104

This looks ugly but it gives you an idea of the flexibility you can get, even if you stick to yaml.

In this example:

- I want some operational DNS client log, but only if they are event id 3008, and aren’t associated with empty or local machine name resolution

- I want everything from the security log

- I want three varieties (

or) of events from the System log

You can nest and and or statements, which gives you some nice flexibility. I err on the side of collecting too much, but these filters at least get me started.

Point to a pipeline and index

Now! You might have noticed something odd in the Security bit:

- name: Security

ignore_older: 168h

fields:

rc_ingest_pipeline: 'windows'

rc_index_name: 'windows'

fields_under_root: true

This is saying that for every event in the Security event log, I want to tack on an rc_ingest_pipeline field, with the value windows (fields_under_root just means I don’t want a nested property). This is how I tell Winlogbeat which ingest pipeline I want to use. In this case, I just have a generic catch-all windows pipeline, but you’ll likely have many others.

Jumping ahead, in the output section, you’ll see that we use the field we just created to point to a pipeline:

output.elasticsearch:

hosts: ["https://REDACTED01:9200", "https://REDACTED02:9200"]

username: "REDACTED"

password: "REDACTED"

ssl.certificate_authorities: ["C:\\beats\\ca.crt"]

pipeline: "%{[rc_ingest_pipeline]}"

index: "%{[rc_index_name]}"

By using "%{[rc_ingest_pipeline]}", we’re evaluating to whatever the value of the event’s rc_ingest_pipeline field is - note that we could have defined different values for different log sources. There are several other ways to route events, including pipelines with conditions, or just a hard coding output.elasticsearch.pipeline rather than using the variable expansion we used.

Do some more client side processing

We’re almost done with the config! There’s one last spot we can have some fun: Processors! In this example, I just remove the message field from some of our most common and verbose events (i.e. those that chew up storage without much benefit):

processors:

- drop_fields:

when:

or:

- equals.event_id: 4624

- equals.event_id: 4634

- equals.event_id: 4625

- equals.event_id: 4648

- equals.event_id: 4768

- equals.event_id: 4658

- equals.event_id: 4776

fields: ["message"]

That’s about it! Now, lets look at that windows ingest pipeline we’re routing some events to.

Ingest pipelines

Ingest nodes let you process things. They’re generally more efficient, but less observable than Logstash pipelines. Do consider the implications; personally, I would tend to lean towards Logstash in most scenarios. Oh well!

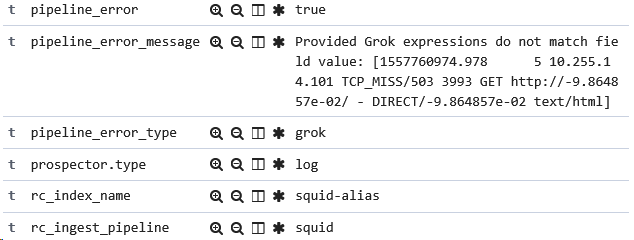

First, we need to define the pipeline. You can use a number of processors, including grok and geopip, but for these events, I just want to run a script, and I want to know if any errors come up (tip: they will, particularly on your first iterations of writing a script)

{

"description": "Process Windows event log",

"processors": [

{

"script": {

"id": "windows"

}

}

],

"on_failure": [

{

"set": {

"field": "pipeline_error",

"value": "true"

}

},

{

"set" : {

"field" : "pipeline_error_message",

"value" : "{{ _ingest.on_failure_message }}"

}

},

{

"set" : {

"field" : "pipeline_error_type",

"value" : "{{ _ingest.on_failure_processor_type }}"

}

}

]

}

All I have is a pointer that says run this script called 'windows'!, and some error handling to give me info on whether an error occurred, the error message, and the error type.

This is important. You want a quick way to see if any events aren’t being processed correctly - by adding these fields, you can search for and alert on any processing errors.

Right. Maybe don’t alert on errors when you fail to grok a field that’s based on user input!

Next, we need to actually define the script. We’ll be using painless. This is a misnomer.

I like a little context. I don’t want the whole message field, I just want a brief what is this event for?. I also don’t memorize enums, so I translate things like logon type.

if( ctx.log_name == 'Security' && ctx.event_data.LogonType != null ) {

def logonmap =

[

'0': 'System',

'2': 'Interactive',

'3': 'Network',

'4': 'Batch',

'5': 'Services',

'7': 'Unlock',

'8': 'NetworkClearText',

'9': 'NewCredentials',

'10': 'RemoteInteractive',

'11': 'Cached'

];

def key = ctx.event_data.LogonType;

def newvalue = logonmap[key];

if (newvalue != null)

{

ctx.rc_logon_type = newvalue;

}

}

# Defining this without initializing it as a map broke things

if( ctx.log_name == 'Security' ) {

Map eventmap = new HashMap();

# subset of event ids for the sake of brevity....

eventmap.put('4720', 'A user account was created.');

eventmap.put('4722', 'A user account was enabled.');

eventmap.put('4723', 'An attempt was made to change an account password.');

eventmap.put('4724', 'An attempt was made to reset an account password.');

eventmap.put('4725', 'A user account was disabled.');

eventmap.put('4726', 'A user account was deleted.');

eventmap.put('4727', 'A security-enabled global group was created.');

eventmap.put('4728', 'A member was added to a security-enabled global group.');

eventmap.put('4729', 'A member was removed from a security-enabled global group.');

eventmap.put('4730', 'A security-enabled global group was deleted.');

eventmap.put('4731', 'A security-enabled local group was created.');

def key = String.valueOf(ctx.event_id);

def newvalue = eventmap[key];

if (newvalue != null)

{

ctx.rc_description = newvalue;

}

}

That’s it! In the script, I make some assumptions and create fields to indicate the description of the event, and to have a friendly name for the logon type. I like context and convenience - you might consider adding much more than this : )

Do note that I’m doing the same thing - assigning a value based on a hashmap - in two ways. I ran into errors when I tried the simplified syntax on a hashmap with ~420 keys, and switching syntax fixed things.

What now?

There’s a lot of flexibility here!

- The same Winlogbeat config syntax for pipelines can be used in Filebeat

- You might explore parsing the windows firewall logs, DHCP logs, and other file logs with ingest pipelines, grok, and painless scripts

- If you care about the location of an IP, geoip is built in now, and is pretty handy (The database is built into Elastic’s container - yay! but you’ll need to mess with templates to indicate the data type - boo!)

- Honestly? You might want to use Logstash. There are more examples in the wild, and you can get data on the performance of each component in a pipeline. The efficiency of ingest pipelines, assuming you don’t need it, is likely less valuable than the benefits you get from using Logstash

- Palantir is bad, but this repo has some very useful data about what you might care about in the world of Windows event logs. I translated some of this to a Winlogbeat config. At some point, it would be awesome if someone were ambitious enough to write an WEF XML to Winlogbeat yaml translation tool : )

- You probably noticed I point Security events to a particular index name. This points us to an index lifecycle management policy. These are useful!

- There’s a ton of interesting tools and blogs out there. Many can be found in security-oriented places. Roberto Rodriguez has some awesome material, including tools like HELK. Pablo Delgado has some handy materials as well

- Don’t restrict yourself to built-in log sources! Be sure to consider integrating other tools like Sysmon into the flow. You might even generate your own event log entries from your various scripts and software, and pull it into Elasticsearch, where you can alert on it, report on it, etc.

That’s about it! PowerShell? Sure. You’re not defining everything in the Kibana dev tools, right? You might have a repo that has ingest pipelines, templates, index patterns, ilm policies, scripts, watchers, and other Elasticsearch or Kibana config that can be defined in code, that you test / lint before pushing to Elasticsearch or Kibana in your build. A glue language like PowerShell is great for this!